In Fall 2020, students led by Associate Professor Louise Siddons created a digital project documenting the art exhibition history of Oklahoma State University, with the assistance of Digital Scholarship Librarian Megan Macken. Students used the digitized archive of the student newspaper, the Daily O’Collegian—today the O’Colly— to construct a database of exhibitions held between 1960 and 1999.

Here on the collection blog, we’re featuring reflective essays written by students about their work on this project, based on the research they did to compile the online exhibition history. This week’s essay is by Samantha Holguin. It has been edited for length and clarity.

I was initially struggling to draw together any conclusions at all between the shows exhibited at OSU in the late 1990s, as many seemed unrelated. One of the first consistencies that became apparent was the common goal that was shared in the student shows as well as the visiting artists. In the year I researched, 1997, there were two major visiting shows, from artists outside of the country. What was interesting was these happened in such a way that they were spread across the school year after long periods of smaller shows from local artists or students and faculty. This actually was quite a clever move because it kept the shows that cycled diverse and allowed for a wide variety of mediums and themes to circulate, keeping the exhibitions interesting to the public.

Many of the organizers were OSU faculty and staff, since a vast majority of these shows were held in the Gardiner Art Gallery, in the art department. On occasion, such as with visiting artists, the shows had been organized by groups like the Tibetan artists, or even a group of potters from Mexico. There were also some shows sponsored by other OSU organizations, such as a show held by Japanese students that served as a fundraiser, or a Native American art show that also served as a way for the artists to make some money. This was quite nice to see, much like the shows themselves, there was a good balance of strictly OSU shows and other exhibits from outside groups, which kept the rotation interesting.

Based on the articles that were published in the O’Colly, the news outlet was strictly reporting on facts. This was perhaps a way to prevent there being any kind of bias over the art show and another subject or organization. In a sense, it made for an even playing ground. One good example of this was even in the Kobe Earthquake fundraiser exhibition, the O’Colly was strictly reporting on the food provided, what was on display, and how refunds would be issued. Rather than emphasis the negative feelings that may have come from there being long lines, they instead made sure to state that there was going to be refunds and even added an apology from the organizer. This also shows that the O’Colly did a good job of interviewing the show’s organizers and other people involved, as some of the student shows included interviews from the students themselves as well as some of the faculty who arranged for the exhibitions.

The first show that I would like to detail was from 1995: the fundraiser exhibition put up by Japanese students at OSU to raise money for Kobe earthquake relief. The 6.9-magnitude earthquake happened on January 17, 1995 in Kobe, Japan. The resulting damage was extensive, and the area along the Osaka Bay received the worst damage. It was also reported that some 140 fires were started because of the event, and infrastructure was totally devastated. This show was a break away from the student and faculty shows during this time, and in fact was a way for students to have a taste of Japanese culture, quite literally. According to the original O’Colly article, students who attended not only had the chance to look at art, but also taste Japanese food and even receive nametags with their names written in Japanese. The exhibition seems to have received some mixed reviews from the student body who attended, as there was a long line to wait in, and during February this would understandably be frustrating for some. However, it seems that there was a push to bring attention to the fun and interactive show and to support a greater cause. The Japanese students who organized this show worked hard to immerse visitors into their own culture and make a memorable experience for everyone who attended, all for a good cause.

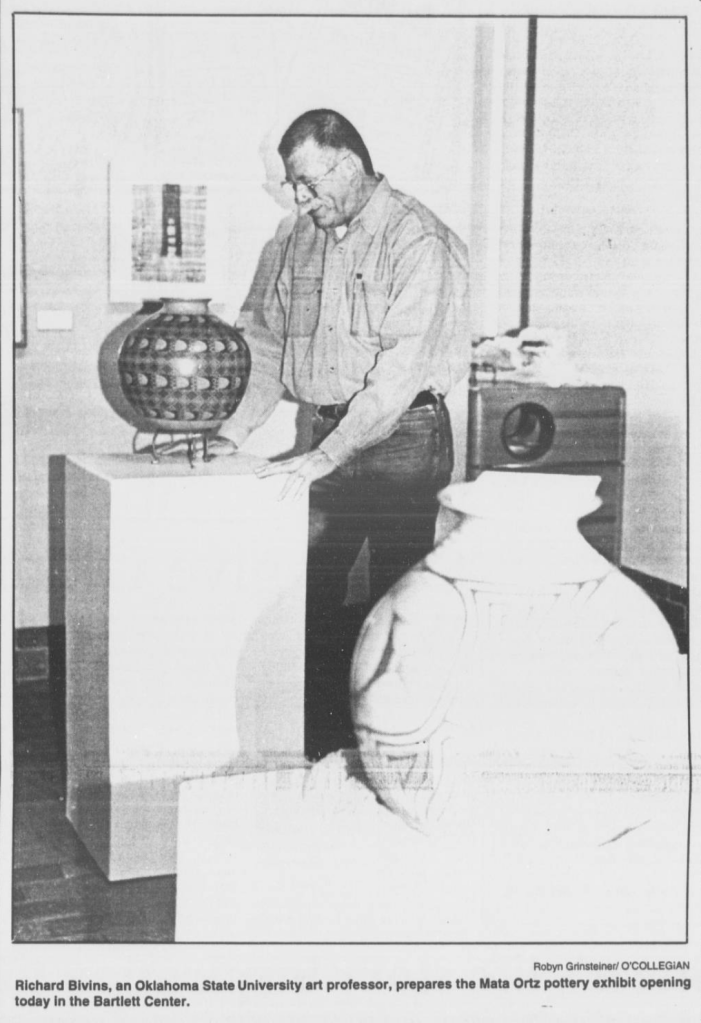

The next show that I was intrigued by was the Mexican Pottery exhibition. This was one of many shows that my group found that was put on by travelling artists from beyond OSU. There was a group of 300 potters from Mata Ortiz, a town of about 2,000, who created pottery as a way to support the traditionally agricultural community. The pottery was a way for the families of the area to make extra money, and a group of 6 potters came to OSU to display their work at the Gardiner Gallery. What was fascinating to me was how the pottery was inspired by a discovery of broken pieces near the village, which led many people to take up this tradition anew that dates as far back as 1175. Many connections can be made, but one of the main takeaways from this exhibition, much like the Japanese art show, is the display of diversity to the students of OSU. Although this was a less immersive experience, this exhibition in fact showed how the functionality of the artwork was what was holding up the economy of the small farm village in Mexico. The art was very popular among many outside of the region and many of the students had likely never even heard of such a small geographical area with a whole group dedicated to making pottery using a technique that was so ancient and labor intensive.

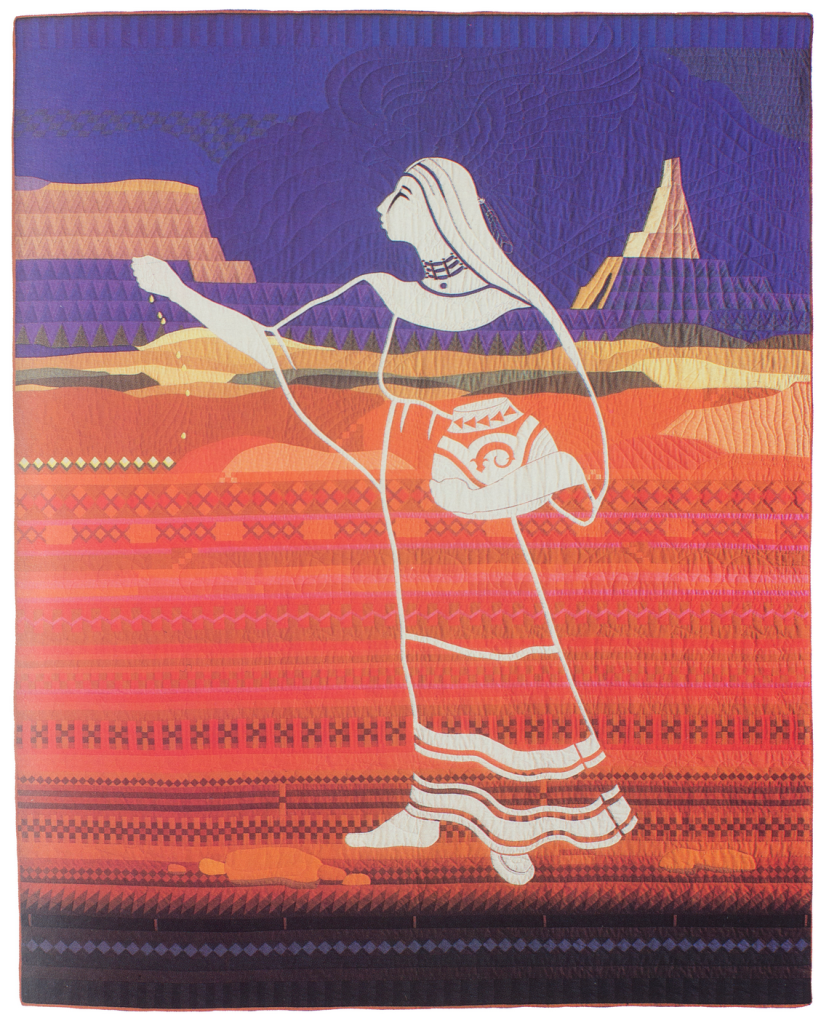

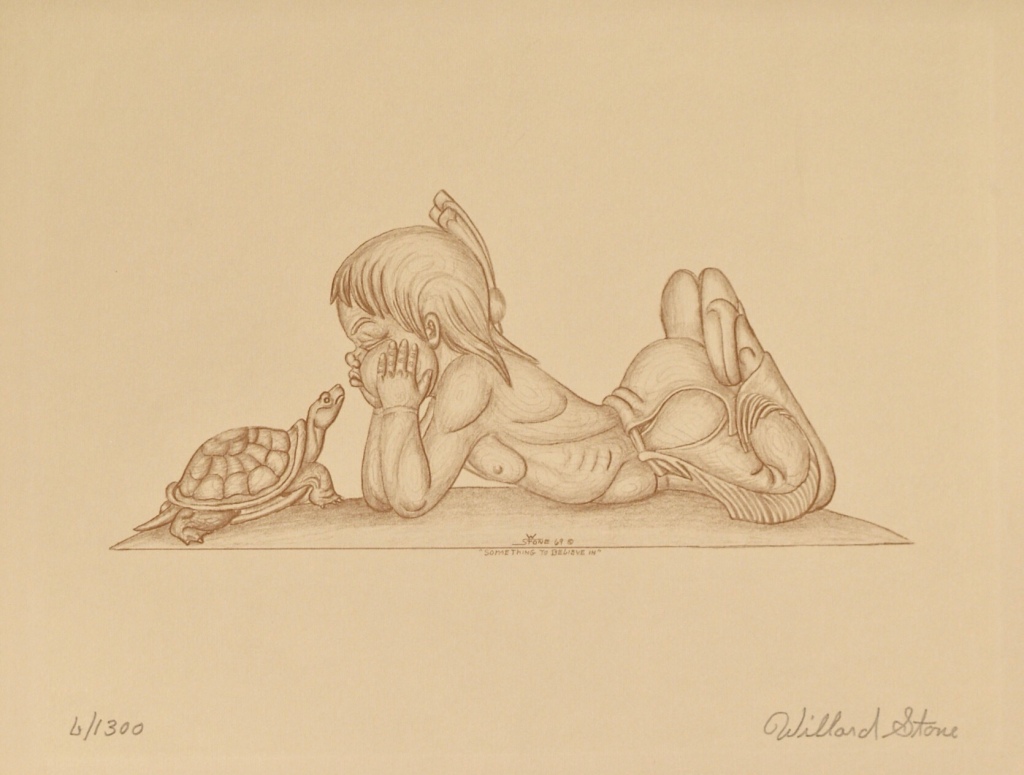

Based on the content that was in the two shows I chose to write about, as well as looking through many of the shows in the database, I noticed that there seems to be a lack of representation in general. While I do appreciate the way that OSU is supportive of their art students with the amount of exhibitions they participate in, it seems to me that many of the shows that were featured by traveling groups were simply showcasing traditional art from other cultures. Without a doubt, there was a wealth of historical art, such as the traditional pottery, Japanese art, and even the sacred sand mandala from Tibet. On the contrary, there seemed to be less attention paid to Native American groups. As I looked at the shows held for Native Americans, many of them were very short and served as a sort of marketplace for students in the Student Union. I feel as if this harkens back to a class discussion we held which discussed patronage and how that can decide on the “authenticity” of art from a culture that is not our own, so to speak. There was a lot of focus on modern art and graphic design, but there was no real focus in these fields and how they interact with people of color. The lack of representation of Native American artists is surprising to me, but I was even more shocked that there was no show that I immediately found in this period that centered on black artists.

The database that was compiled allowed me to see what OSU has focused on in the past from an exhibition point of view, but it has also shown me where it has fallen short. If it was up to me to propose a new show, I would want there to be a show more thoroughly dedicated to contemporary work by Native American or black artists. Rather than have a show on their historical art, like pottery or weaving, I would like for there to be something that shows their work in the modern era and how it may address their places in society. This may also apply to the LGBT+ community if we are also discussing diversity and how that can be better represented in the exhibitions that are held on OSU campus so that there is more cultural variety in these shows. While there was an attempt to bring awareness to many cultures during the time period which I researched, there was a lack of real diversity that goes beyond the more recognizable pieces that are associated with these cultures. Thus, it would have been more beneficial for the school to have had a show that encompassed these groups of people in a way that would not be potentially seen as stereotyping.